What food is healthy to eat? As a dietitian, I get asked this a lot.

There are so many different ideas and opinions, and nutrition research is constantly changing.

You’ve probably heard you shouldn’t eat eggs, they have too much cholesterol. Maybe you’ve also heard they’re a great source of protein.

Did your physician tell you a low-fat diet is best for heart health, but then your friend said the high-fat Keto diet is shown to improve health?

Not only is this “health” information inconsistent and confusing, but it also misses the point.

Asking, “What food is healthy to eat?” especially without context, isn’t helpful nor accurate, and it’s potentially harmful.

The information discussed here is only the tip of the iceberg. It’s certainly not all-encompassing, but I hope it provides another perspective and provokes greater thought. So here are some reasons why labeling food as “healthy,” especially as a blanket statement, misses the point.

Ignores access to food (quantity and variety)

Using the term “healthy” specifically related to food or a way of eating assumes a lot of privilege and fails to recognize the many other factors that affect health. This includes an individual’s access to both variety and quantity of food.

When we ask, “what food is healthy to eat?” we completely ignore that some people don’t have access to enough food. According to the compilation of research reviewed in The Grocery Gap, low-income zip codes have 25 percent fewer chain supermarkets and 1.3 times as many convenience stores compared to middle-income zip codes. Predominantly Black zip codes have about half the number of chain supermarkets compared to predominantly White zip codes. Predominantly Latino areas have only a third as many.

When someone has less access to food, the healthiest thing for them to eat is the food that’s available. They need to eat enough and try to get a variety of nutrients from the food they do have. That might mean that any type of breakfast cereal is a great source of iron and folate, and therefore a “healthy” option. The same applies to other grains like white pasta and rice that are often vilified.

Describing food as “healthy” or “unhealthy” places the burden on the individual to make “healthy” choices. Access to food is not an individual issue. If we want to improve health, we need to focus on getting people an adequate amount and variety of food.

Labeling food as “healthy” leaves out cultural diversity and food preferences

We often teach “healthy” eating through a Eurocentric lens. This is not to say that one group of people can only like one type of food. That type of stereotype is also not helpful. However, a lot of our “healthy eating” standards lack diversity.

We recommend people eat cottage cheese, kale smoothies, and chia seeds. We don’t typically talk about the benefits of collard greens, okra, ceviche, or mole sauce.

Instead, we give standard advice like switching from white to brown rice or fried chicken to baked chicken breast. These swaps also miss the bigger picture. We don’t address how individuals make and eat their meals if we tell them to just switch out an ingredient.

For instance, the standard of health in the U.S. is represented by MyPlate: fill half your plate with produce, the other with part lean protein, part whole-grain. Telling different cultures to simply sub out the quarter plate of whole-grain pasta with brown rice, a tortilla, or grits doesn’t necessarily represent how that culture typically eats a meal.

They might have a bowl of rice covered with a mix of potatoes, tomatoes, chicken, onions, and curry sauce. That’s far from MyPlate’s “healthy” eating picture of plain baked chicken breast, a quarter plate of brown rice, and a half plate of salad or fruit.

A standardized approach to healthy eating leaves out a wide variety of cultures and individuals. We can’t tell people to add flaxseed to their oatmeal and eat non-fat yogurt for a snack if they don’t enjoy those foods or are unfamiliar with them. If people don’t create their meals that way, we can’t tell them what their plate should look like.

A black and white picture of healthy eating is limiting. If white rice is the vehicle to get in sushi fish or a curry sauce full of vegetables, but we’re telling people to stop eating white rice, we’re amiss.

Our ideas about healthy eating have to become more inclusive or they’re not actually helping people make true change to improve their health.

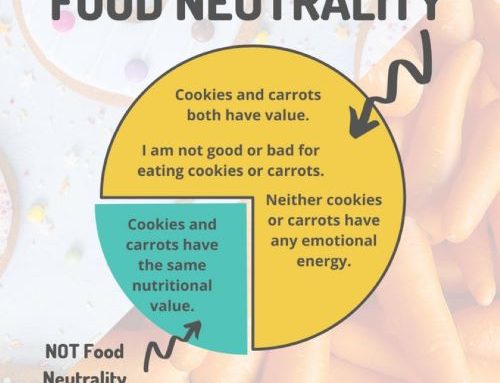

Labeling food as “healthy” contributes to good food/ bad food thinking, and food isn’t that dichotomous

When we describe food as “healthy” we automatically create binary categories: good/bad, healthy/unhealthy. Placing food into categories is too simplistic for the complexity of food. It ignores the varying levels of nutrition that individual foods offer.

Food has a variety of nutrients and different processes for including them, such as fortification or freezing to maintain nutrient status. Some foods offer more macronutrients, such as carbohydrates from bread, while others offer more vitamins and minerals, like broccoli. Neither of these is inherently good nor bad, they just offer different things.

Broccoli is typically labeled “healthy” because it provides vitamins and minerals. Ice cream is usually categorized as “unhealthy” because of its fat and sugar (carbohydrate) content. However, the human body needs fat and carbs, and ice cream also provides some protein, calcium, and phosphorus.

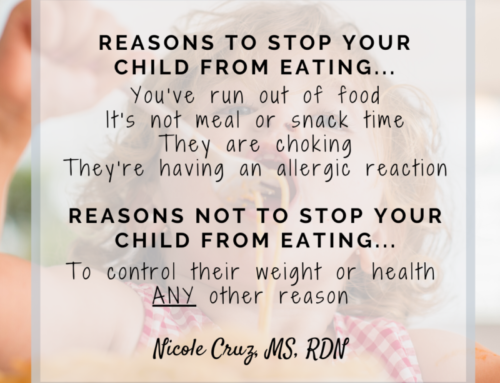

Further, health is more than what we eat. Sometimes we need to prioritize things other than the nutrients in food. For instance, to make a healthy choice you might need to buy a frozen pizza so you can get to sleep earlier than staying up to prep dinner for the next night. Maybe you reduce your stress level by going through the drive-thru after practice one night instead of going home and making dinner. Or maybe your selective eater only eats chicken nuggets for protein, then that’s the healthiest way to get in protein.

Additionally, labeling foods as good and bad contributes to a binary label that doesn’t promote a healthy RELATIONSHIP with food. This is true for all of us, and especially for children.

Kids think in concrete terms.

They internalize:

If I eat “bad” food → I’m bad.

Then those foods become more desirable and the child feels guilty for eating them. Or they internalize eating “bad” food as shame and something they should hide. They also might start to fear “bad” food and go down the rabbit hole of eliminating all “unhealthy” foods and restricting their variety and intake.

None of these scenarios are healthy ways of behaving with food. They set up food to have moral value and create guilt and shame. They add more stress and have the potential to create physical complications as well.

Food is complex and the way we interact with it is diverse. We can’t put it into binary categories. When we ask, “what food is healthy to eat?” we’re asking the wrong question.

Our ideas about “healthy” eating have to be inclusive. If they’re not including access to food, cultural diversity and individual preference, and the spectrum of nutrient needs and other factors of health, we’re missing the point.

Leave A Comment