Talking to kids about food and nutrition seems simple, but it’s actually tricky. It’s confusing because typical nutrition education for children focuses on healthy eating and how food affects their body, but that’s abstract, and children are concrete thinkers.

This is one of the many reasons that traditional nutrition education, and the way we talk to kids about food in general, misses the mark. It’s the reason my three-year-old came in crying, scared he was going blind. When I asked him what was wrong, he sobbed, “Because I heard carrots are good for your eyes and I didn’t eat any today. Am I going to be blind?”

What Typical Nutrition Education Gets Wrong

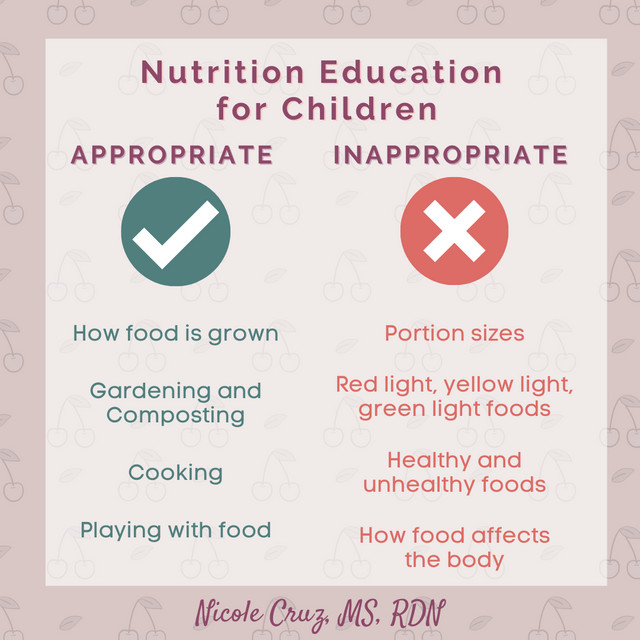

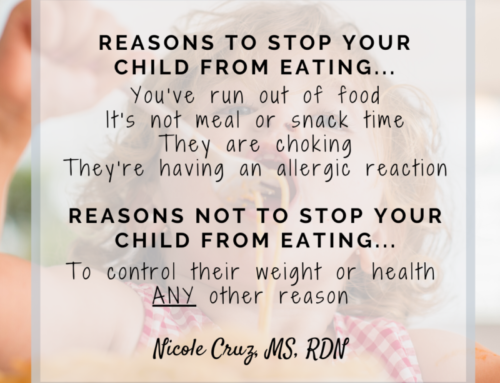

It’s not that teaching children about nutrition is completely wrong, but traditional education about good food/bad food, ‘sometimes’ foods, moderation, and how food affects the body is inappropriate, especially for young children. We’ll get to how nutrition education evolves for older children in a bit. For now, let’s look at why typical nutrition ed is pointless at best and harmful at worst.

Nutrition is an abstract concept.

Children are generally concrete thinkers until they are 11 or 12 years old. Some children don’t develop advanced cognitive thinking until even later and few kids can think abstractly a bit earlier. Concrete thinking is literal thinking. It’s focus is experience: what one can see, touch, hear, smell, or taste. Abstract thinking, on the other hand, involves application. It’s a thinking process.

Traditional nutrition education is abstract because it involves using concepts you can’t see. First, you can’t see that carrots have Vitamin A. Then you have to apply that your body extracts Vitamin A from carrots to keep your eyes healthy. On top of that, you have to understand it’s ok if your body doesn’t get much Vitamin A one day, your eyes will still be ok, and that other foods also contain Vitamin A. This explains why my three-year-old, who also can’t grasp that macaroni is a type of pasta and not just macaroni and cheese, came crying about going blind from not eating carrots.

They think in literal terms.

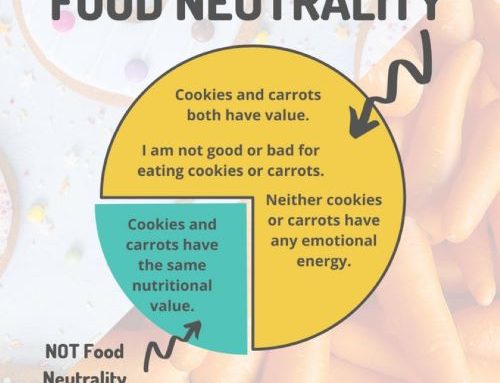

They can repeat back facts like protein helps your muscles, or oranges have Vitamin C, but they can’t apply them in a meaningful way. Children’s concrete thinking makes nutrition education pointless and potentially harmful. Telling a child a food is a ‘sometimes’ food or ok in moderation, isn’t applicable, and it has the potential to cause harm. It creates good/food, bad/food mentality. Kids think literally, so they think, “If I eat a bad food, I’m bad.” This is why nutrition education is the breeding ground for guilt and shame related to eating.

Because children are concrete thinkers, they can’t use nutrition concepts to make food choices. This is why it’s the parent or caregiver’s job to decide what food is offered. and it’s the child’s job to listen to their body and decide what to eat from what’s provided. For more on this feeding philosophy, read The Division of Responsibility in Feeding. When we educate children about nutrition, we’re forcing them to enter adult territory, and that’s not their job because they’re not ready for it.

Nutrition education focuses on external reasons for eating.

Children are naturally intuitive eaters. When given access to a variety of food, they naturally balance out their intake, typically over the course of a week. Children (and adults) stop eating intuitively when something interferes with that ability.

Interference might be:

- Eat two more bites before you can leave the table.

- You have to finish your dinner if you want dessert.

- You have to try at least try one bite of everything.

- You’ve already had enough pizza. If you’re still hungry you can have fruit.

- We need to eat ‘healthy’ foods.

All of these statements move the focus from the internal locus of regulation to thinking about external reasons to eat certain foods or amounts.

Other things that create interference include:

- eating difficulties, such as chewing or swallowing ability

- trauma, related to eating or their body (i.e. food allergies)

- diets

- emotional dysregulation or learning to use food for coping

Since children regulate their food intake on their own, nutrition education that focuses on serving sizes, what to eat more of, or what not to eat, distracts them for their ability to eat. For instance, ‘healthy’ eating is often geared toward fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins. However, all people, but children especially, also need fat. And they don’t understand moderation or sometimes. So a child who would naturally add cream cheese to a bagel, or peanut butter to an apple, is left second-guessing if that’s ok, a bad food, or too often.

When my oldest was six, he came home from school and told me, “Pizza is unhealthy.” I asked more and he shared that a guy came to their school to talk about being healthy. He told them, “Pizza is ok sometimes, but not too often, because it’s greasy. And if you want to make it better you should add vegetables and have it on whole wheat crust.” His job is not to worry about how often he’s eating pizza or if he can make it ‘healthier’. That’s my job as his parent. He’s not responsible for the food and it distracts him from listening to his own internal regulation, guiding hunger and fullness.

So, if we don’t teach about nutrition, how do kids learn what to eat and how to be healthy?

What Is Appropriate Nutrition Education for Children

Nutrition education evolves as children evolve. It’s geared toward their ability to process information in a meaningful way while not doing harm. The way we talk to young children about food can always be applied throughout the life span but also added on to. And one of the key components when teaching about nutrition should be that it’s always done through a weight-neutral lens as opposed to being about ‘healthy body size.’

Food should be about fun, experiences, and internal regulation and guidance. Also know that you role-modeling what’s included at a meal and enjoying food, is also the best ‘education’ for them.

Baby and toddlerhood

Eating food. Playing with food. Reading about food. Making a mess with food. Having fun with food. Having the autonomy to eat or not.

Young childhood (approximately 3 – 7 years old)

Everything mentioned for babies and toddlers still applies for young children. However, they’re more capable of additional concrete activities. They can learn about and get involved cooking, gardening, and composting. They can do art with food, such as cutting up fruits and vegetables to form pictures or paint with the produce. The goal is to create a pressure-free environment to get familiar with different foods and have fun with them.

Middle childhood (approximately 8 – 11 years old)

Again, everything prior still fits! Now children can start understanding food groups a bit more, such as what foods fit into the protein or fat categories. However, we still avoid relating that to health information, how it applies to the body. For a great nutrition lesson, check out Anna Lutz’s lesson on The Edible Parts of a Plant.

There are times when it might seem appropriate to share food groups for specific situations, such as you need protein and carbs for your soccer game today. Even when doing this, try to make it as concrete as possible. Come up with a list of snacks that show them exactly what they might eat. You can brainstorm together. Then let them choose to eat or not eat, and encourage them to notice how their body feels when they do or don’t eat the protein/carbs. Kids need experiences, not lectures.

Adolescence (12 – 19 years old)

The teenage years are the time when kids finally process abstract concepts. This is the period where gentle nutrition is appropriate. You might teach your child how to put together multiple food groups at a meal and how carbohydrates, protein, and fat work together to make food more satisfying and keep them full. At this point, we provide nutrition information in a neutral and positive way, and still focus on what to include, not exclude, unless there is a food allergy or other warranted reason to exclude foods. Teenagers are also starting to take on more adult roles, such as putting together their own meals and snacks. This is why gentle education is also appropriate.

Take home point: Children cannot understand nutrition education until they’re in adolescence. They need to have a healthy relationship with food through fun, exposure, and eating intuitively, to apply nutrition information in a positive and helpful way, without guilt or shame. Focus on experiences and allow your child to listen to their body.

If you wonder how to do this, check out my online workshop: Stress-Free Family Eating

Leave A Comment