My child gained weight. He also “gained” height.

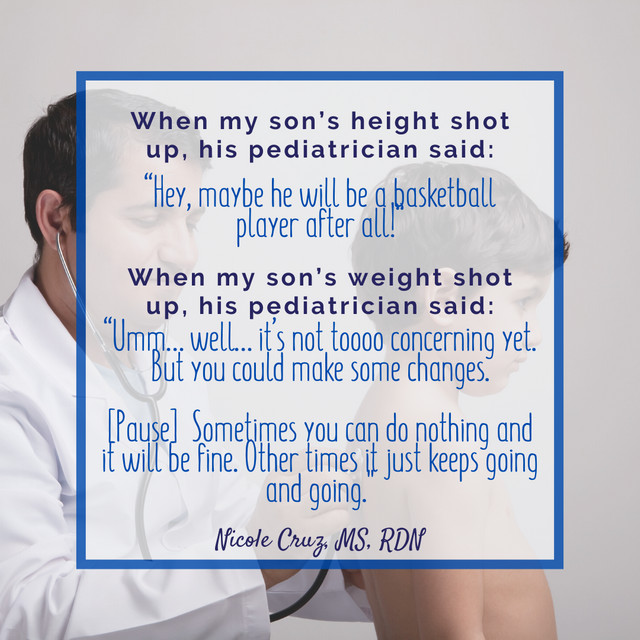

When my son had his yearly doctor’s appointment a few years back, his height jumped in percentiles. Our pediatrician responded with what you might even consider accolades: “Hey, maybe he will be a basketball player after all!”

His comment was light-hearted and neutral, maybe even positive.

Then, at my son’s visit a couple of weeks ago, our pediatrician was looking over my son’s chart and plotting his growth. He responded with, “His weight really jumped up.”

I replied with a simple, “Yes.”

He said, “Oh, so you’re aware?”

Me again, “Yes.”

I could tell my son’s grown recently, just by looking at his recent body changes.

I could feel the tension in the room rising. This physician knows what I do for work and he knows my stance on weight. He stuttered a bit then said, “Umm… well… It’s not toooo concerning yet, but you could make some changes.”

Me: “I won’t be making any changes.”

He paused and then said, “Sometimes you can do nothing and it will be fine. Other times it just keeps going and going.”

Sadly, this is not uncommon.

Why my child gained weight and I’m not making any changes.

I’m grateful I have the knowledge and experience to provide education to our pediatrician and feel confident in feeding my child exactly as I always have.

As a dietitian, I was introduced to Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility (DOR) years ago in my first job right out of college. I worked in the outpatient, education sector at a local hospital, and I was assigned to teach a class to parents and their “overweight” children.

My colleague was in charge of the physical activity portion, and I was supposed to teach the children and their parents about healthy eating through a traffic light system: red light, yellow light, and green light foods.

Luckily, my partner was familiar with Ellyn Satter’s work, and said, “We can’t teach this.” She and I then redesigned the entire course to teach DOR to the attending parents.

The Division of Responsibility

In short, DOR designates the child’s job and parent’s job in feeding.

- Parents are responsible for the what, when, and where of feeding.

- Children are responsible for how much (if anything) they eat from what’s provided.

In other words, once you put the food out, your job is done. We follow this research-based philosophy in feeding because it assists in raising competent eaters. Competent eaters have overall better health outcomes, a more varied diet, and a positive relationship with food and eating, among other things. This method of feeding also creates more joy and less stress for everyone!

To read more about it, check out The Division of Responsibility in Feeding

Problems With the Doctor’s Recommendation

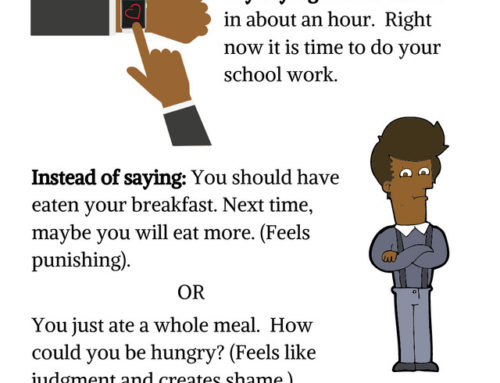

- He didn’t once ask me about my son’s eating patterns, activity level, mood, or behaviors. He didn’t ask me if I have concerns or if anything changed recently. Instead, he made his recommendations purely on one piece of data that’s not even indicative of his health. My son happens to be active and eat a variety of foods. He’s an overall happy child who’s social, thoughtful, and has a range of interests. These are the important things! However, he was only concerned that my child gained weight.

- He did this in front of my son. I can’t imagine the shame and embarrassment for so many kids, especially if their weight’s much “worse” (not my belief). If a physician has a concern about a child’s weight, they should discuss it in private with the parent. Body shame is predictably and directly related to depressive symptoms. It also perpetuates weight gain.

- This was one appointment with limited information. Since when do we make assumptions based on one piece of data? Children tend to grow at different rates both for weight and height. With one piece of data, we don’t know my son’s trend. We don’t know if his weight accelerated quicker than his height over the last month and then his height will catch up. We also don’t know if he’s going to remain at this percentile for weight with it just “going and going.” We don’t know anything from one piece of data and recommending changes is negligent, especially when the consequences of limiting food or making dietary changes have the potential to be quite harmful.

- This is weight stigma. My son’s pediatrician looked at one piece of information, weight, and made assumptions: something needs to change, his body is not ok, bodies can and should be controlled. He suggested one body type is better, healthier, or preferable; and he prioritized weight over all other aspects. What if my son was struggling with grief, depression, or an illness? He didn’t address any of these – just “fix” the weight.

- BMI and weight are not indicators of health. BMI (Body Mass Index) and weight do not provide any information about one’s health. All people, including children, have different body types and sizes. Just because someone is at the higher end of the weight spectrum does not mean that they’re unhealthy or their weight needs to change. If your child’s weight is consistently jumping percentiles, you might want to assess if there are any underlying issues, such as emotional or medical concerns. However, if your child has always been in the 90th-plus percentile for weight, that is likely their genetically determined weight. For more on weight and health, read this short excerpt on Health at Every Size™.

What you can do to protect your child

- Do not discuss weight in front of your child. Call or email ahead of time. Ask the front desk or nursing staff to put a note in the chart to not discuss weight. If your doctor starts while you’re in the office with your child, ask them to discuss any concerns with you privately.

- Follow Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility in feeding. Let your doctor know that you appreciate their concern but you follow a research-based model for feeding called the Division of Responsibility. Continue to follow the DOR without trying to control your child’s weight.

- Provide resources for your physician: Health at Every Size by Lindo Bacon and Ellyn Satter’s Your Child’s Weight: Helping Without Harming.

- Discuss the visit with your child. If you have a difficult interaction, discuss it with your child. Open up the dialogue for them to ask questions. Ask them how they feel about it. Remind your child that bodies come in all shapes and sizes and all bodies are good bodies.

- Find another pediatrician. If it’s an ongoing issue, you might need to seek out another physician.

Lastly, if you or your child have been shamed for your weight, I’m sorry you had that experience. You deserve better care and treatment. If you struggle with your relationship with food, or the way you feed your family, make changes that align with creating a healthier and intuitive relationship with food. You don’t have to try to control your weight. My child gained weight, and I’m not making any changes.

If food is a struggle in your home, or your concerned about your child’s eating patterns, grab my online workshop:

Leave A Comment